On Being Ill

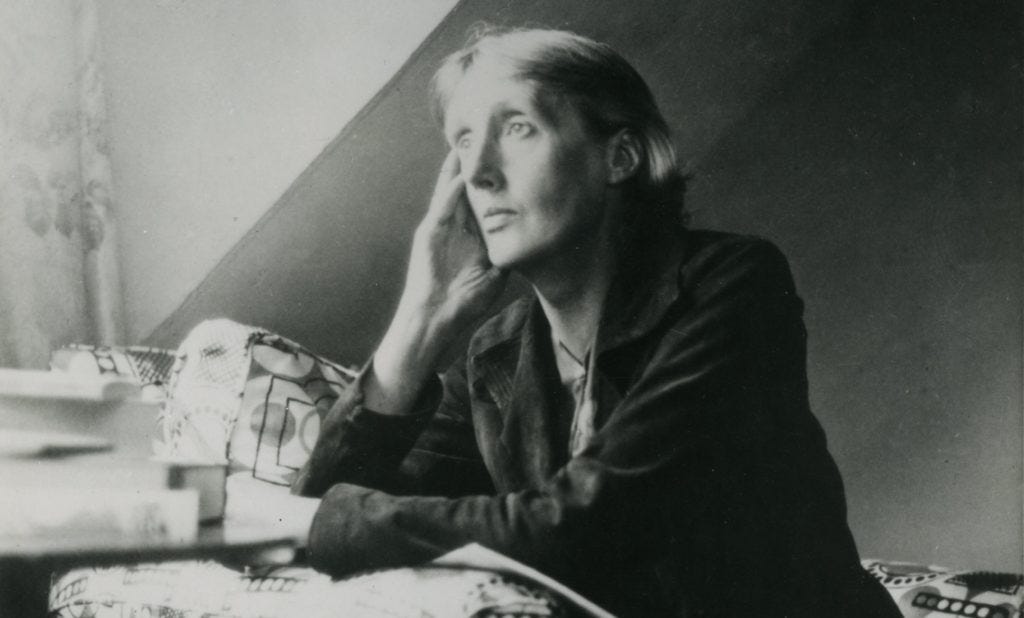

Virginia Woolf, for better or worse, never stops being relevant. And no wonder why. She has looked in the face of things that scare the daylights out of most people and written about them in exquisite words.

When I first started reading her, I used to reach towards her diaries and her novels, very selfishly and purposefully. I wanted comfort. I wanted to read the words of someone wiser and older who understood. I didn’t seek plot or entertainment; I sought sustenance.

Needless to say that when I found myself in the throes of a diagnosis that turned my world upside down, Woolf was again, the first person to have any inkling of what I felt. I tried other places, other people. But it was Woolf saying that illness is the great confessional that embalmed me.

In her essay titled “On Being Ill”, published in 1926, Woolf talks about the lack of body in literature.

“Literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear, and, save for one or two passions such as desire and greed, is null, negligible and nonexistent”.

Fortunately for all of us, this is not entirely true anymore. We do have a plethora of great memoirs, novels and essays focused on people’s experience with being ill.

But at her time, this was not the case. Save for a handful of writers, nobody had ever dared to directly address and publicly reveal their fits of bodily pain that were the cause of many sleepless nights. It was not so that her contemporaries were never ill to the degree that Woolf was. Hemingway was an alcoholic with severe depression. Fitzgerald was an alcoholic and a chainsmoker, DH Lawrence was plagued throughout his life by tuberculosis. Joyce had a host of optical issues that left him writhing on the floor. They were all pretty damn sick. And while they probably had their own way of channeling that into their art – one could hypothesize that Lawrence’s obsession with vitality was precisely because of the lack of it in his own life – none did it more courageously than Woolf.

Woolf knew that writing about illness is an especially daunting thing. She writes

“- it requires the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth.”

In spite of our relative expansiveness of illness-focused literature today, this is still true. It has never been easy to write about one’s hysteria over the shadow of a symptom or the shame of being in a body that makes an outcast out of you. It will never be easy. It flays you open to a host of responses that are all so detestable in their own way: fear, contempt, pity. No one desires to be subjected to that, least of all writers with their large, masculine egos.

Writing is often a means of being in control; writing about illness is terrifying because it does away with that illusion. You are in control of what you write but it’s still a massive act of vulnerability; it can inalterably change the way people think of you. You lay supine to the world, a stance that can destroy anyone without that reason “rooted in the bowels of the earth.”

Since the early 20th century, we have made some considerable leaps in medicine. But, I believe, we are still in the nascent stage of it. Our economic infrastructure hardly supports innovation and research or equal opportunities for all; at least not commensurably to profits. We suffer on a species level because of this in every crisis, whether that is medical mysteries or tackling climate change or eliminating poverty.

My point is that Woolf remains relevant because the world remains fucked up, which is not a fact that has changed much over the last century. But I like - or want - to believe that illness can be every bit as valiant and transformative and worthy of our attention as Homeric epics. I want to believe that illness can be a lighthouse in disguise, guiding us closer to our mysterious destinations.

Am I just trying to endow meaning to what is actually just senseless pain? Am I trying to force a meaning on a universe that is meaningless? Possibly. I do not claim to be a hard-wrought rationalist. Illness and death, after all, have that effect on you. Myths and fairytales become less hard to believe. Make you susceptible to magical thinking. But if it’s an illusion, I think it’s a pretty sustaining one. We don’t need it to be ontologically true; we only need it to work.